Honestly, after being a Mac guy since around 1994, I’m a little tired of Apple.

Let me clarify that from the start: this isn’t about hating their products. I still love my iPad—nothing else matches its blend of fluidity, tactile control, and elegant software. It’s a pleasure to use, whether I’m sketching, note-taking, or simply reading in bed. My Mac remains one of the best machines I’ve ever owned: a workhorse with grace, a tool that’s as intuitive as it is powerful. Even the iPhone, for all its lock-ins and limitations, still offers the most polished mobile experience out there. I don’t have a problem with Apple’s devices. And I’m neck-deep in Apple’s ecosystem; I love my Ted Lasso and I have literally thousands of dollars spent on movies which are exclusively on Apple’s platform.

What I’m tired of is the company behind them.

Apple, the corporation, used to stand for something. At least, that’s how it felt. For those of us who joined the Apple ecosystem in the ’90s and early 2000s, it wasn’t just a brand—it was a declaration of values. Apple represented creativity, individuality, a kind of noble rebellion against the gray corporate blandness of the Microsoft era. Owning a Mac wasn’t just about specs; it was about choosing design over drudgery, elegance over conformity, and human-centric computing over corporate compromise. That’s what made us stick around. That’s what made Apple different.

But somewhere along the way—somewhere between record-breaking quarterly earnings, trillion-dollar valuations, and executive reshuffling—Apple lost something. Maybe it’s inevitable for any company that becomes a global behemoth. Success has a way of blunting ideals, especially when those ideals get in the way of shareholder value. How can you tell the most successful company in the world that they’re doing something wrong? And now, as I sit with the newest Apple devices in front of me, I find myself wondering: what exactly am I supporting when I keep buying into this

Because let’s talk about support. Apple used to be legendary for customer care. If something broke, you booked a Genius Bar appointment or go to an Apple Service Provider. You walked into a space that felt helpful, human, even joyful. You’d meet someone who knew the product, who’d listen to your problem, and who’d often go out of their way to fix it—even if the warranty had expired. You felt like you were dealing with a company that cared, not just about your business, but about your experience.

Today? Support feels transactional at best, outright obstructive at worst. Try calling AppleCare and you’ll get funneled through a maze of automated prompts before being connected to someone reading from a script. Go to a store and you’ll be lucky if your appointment isn’t delayed, rushed, or redirected. Genius Bars are crowded, understaffed, and strangely corporate now. That sense of goodwill—the sense that Apple had your back—has eroded. Replaced by policies, queues, and thin smiles. They’ve even dismantled the Apple Service Provider network – just pissing decades of goodwill down the drain.

Then there’s strategy. Apple’s strategy used to be visionary. They weren’t chasing market share; they were setting the agenda. Think of the iMac’s bold design, the iPod’s intuitive wheel, the iPhone’s touchscreen revolution, or the MacBook Air being pulled from a manila envelope. These were bold, clean statements. Apple took risks, often standing firm against trends that diluted user experience. No bloatware, no cheap compromises, no fragmented ecosystems.

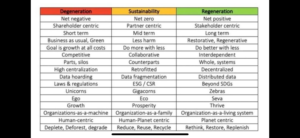

But in recent years, Apple’s strategy has felt more like a hedge fund’s playbook. Services are the new goldmine, and everything is being bent toward recurring revenue. Apple One bundles, iCloud+ upsells, app tracking ads (which somehow aren’t tracking because they’re from Apple)—it all feels like death by a thousand microtransactions. Instead of delighting users, Apple is increasingly nudging them, corralling them, and subtly extracting just a bit more every month.

And what about the App Store? Apple’s “walled garden” once protected users from malware and delivered a curated, high-quality experience. Now, it feels like a toll road. Developers pay 30% to be there. Users pay more because developers have to factor in that cut. Rules are inconsistently enforced. Competing apps are throttled or shadowbanned. And heaven forbid you try to direct your users to an external payment page—that’ll get you flagged, penalized, or booted. The garden has grown thorns, and they’re facing inward.

Apple has gone to court defending this ecosystem, claiming it keeps users safe. But let’s be real: it keeps Apple wealthy. What once felt like thoughtful curation now feels like gatekeeping. Monopolistic behavior dressed up in brushed metal. Apple should have been taking the lead in opening up the AppStore rather than having to have compliance forced upon them. They used to be the thought leaders here. Ironically, opening up and reducing fees would be the number one remedy to bad press and dissent from EPIC and other developers. It would kill third party AppStores overnight. Apple always said that the App Store paid its bills but wasn’t a profit centre. That was plainly bullshit.

And that leads to the bigger problem—the moral collapse of Apple’s identity. Once, Apple took risks for principle. They stood up to the FBI when pressured to break encryption. They invested early in renewable energy. They pushed accessibility forward with real innovation, not just empty press releases. These things mattered. They built trust.

But that trust is fraying.

Tim Cook still talks the talk on privacy, but Apple’s own ad business is growing. They claim to protect users, yet allow certain companies privileged access to analytics. They preach freedom, while locking down repairs, discouraging right-to-repair initiatives, and serializing parts to prevent third-party fixes. They claim neutrality, yet lean heavily into policies that suppress competition. And they do this all while wearing the costume of virtue.

If Apple has a conscience left, it seems to reside in Phil Schiller—a man who, for all his faults, still seems to care about the soul of the company. The rest of the leadership team looks like a lineup of financial engineers and logistics optimizers. Gone is the Steve Jobs-era obsession with wonder, with meaning. What remains is operational efficiency, brand preservation, and market dominance. It’s sterile. It’s dull. And it’s deeply, deeply disappointing.

So I’ve found myself doing something I never thought I would: looking east. Toward Huawei.

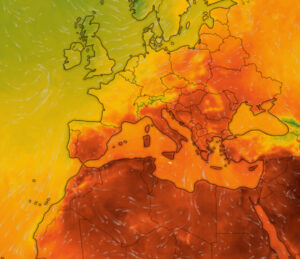

Yes, I know the reputation. Yes, I understand the controversy. But here’s what I also see: a company that’s been forced—by global politics and trade wars—to stand on its own. A company that has, under immense pressure, built an entirely new operating system: HarmonyOS. A company that didn’t cave or crumble when access to Android was revoked, but instead innovated, creating something new, self-contained, and uniquely Chinese. Now that the Cheeto in Chief has forced the revocation of Windows OS licensing to Huawei, they’ve responded with their own operating system – and the success of it is entirely due to the sanctions placed on China. Please note that- this sanction is not a Republican or Democrat thing; it’s an American thing. They put them there to stop someone else competing; because if there is one thing a capitalist hates, it’s competition. So, Huawei built up their OS and market in their home market of, I dunno, a billion or so people. We can listen to people tell us that China is data mining everything we send in a Huawei device. And we can point out that the FBI and the NSA have pretty much unfettered backdoor access to Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook and Google. I’m not even sure I trust Apple when they say they’re resisting this stuff. Trust,that’s the thing.

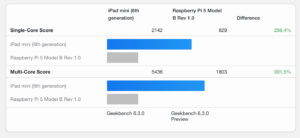

Knowing what you’re getting appeals to me. Not because I think Huawei is the saviour of tech, or because I’m blind to their ties to the Chinese state. But because they’ve built something different. They’ve had to. They weren’t allowed into the club, so they built their own house. And from what I’ve seen, that house has some compelling architecture. Smooth device interoperability. Elegant UI choices. Custom chipsets. An ecosystem that isn’t just a clone of Android or iOS but its own hybrid.

That’s exciting in a way that Apple used to be.

More than that, I’m tired of US tech bullying the rest of the world. I’m tired of their sanctimony, their assumed moral high ground, their soft imperialism wrapped in glossy product launches. Their hard imperialism with a dominant military-industrial complex when it’s disobedient poor people. The US government uses sanctions like a cudgel, attacking companies like Huawei under the guise of national security while quietly supporting the surveillance capitalism of Silicon Valley. It’s hypocrisy at scale.

And Apple, increasingly, feels like a cultural arm of that same establishment. Their policies, their posture, their entire outlook feels aligned with the narrow interests of Washington, Wall Street, and the West Coast elite. They promote individual freedom but lock you into their cloud. They preach openness while maintaining one of the most restrictive app ecosystems on Earth. They wave the flag of “user trust,” but act like a monopoly with no serious accountability.

Frankly, I’m done.

If the EU had any backbone, they’d tell the US to pack up their military bases and go home. Europe should be prepared to stand alone. Let Europe grow its own digital sovereignty. Let a thousand new tech ecosystems bloom—some in Europe, some in Asia, some in Africa. We need alternatives. We need choices. We need companies that don’t just pretend to care, but actually serve the regions they operate in.

I know Huawei isn’t perfect. No company is. But right now, they feel hungry. And hunger builds interesting things. Apple, by contrast, feels bloated—complacent, defensive, protective of a legacy they’re no longer living up to. They still build beautiful things. But the heart that once beat behind those products feels faint, remote, and increasingly artificial.

What I want is the return of vision. Of boldness. Of companies that build for humans, not shareholders. Of ecosystems that reward creativity rather than locking it behind a paywall. Of technology that serves people, not power.

Right now, I don’t think Apple knows what it wants to be. It’s rich, it’s admired, it’s envied. But it’s also unmoored. The sparkle has dulled. The soul has faded. What remains is machinery: effective, powerful, but cold.

I still use Apple products. But I no longer believe in Apple.

And that, more than anything, is why I’m looking elsewhere.

Maybe it’s time for something new. Maybe it’s time to break the spell.

Maybe it’s time to try Huawei.