Andrew Leonard sent this link: Translink Annual Report 2010-2011

Much of the report is given up to Translink talking about new ways they have introduced to incrementally reduce the cost of transport including weekly, monthly and annual tickets, maintaining a network of 900 top-up points across the province and tax incentives. All of this expense and effort could be wiped out with FreePublicTransport.

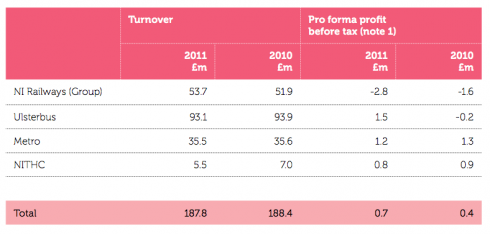

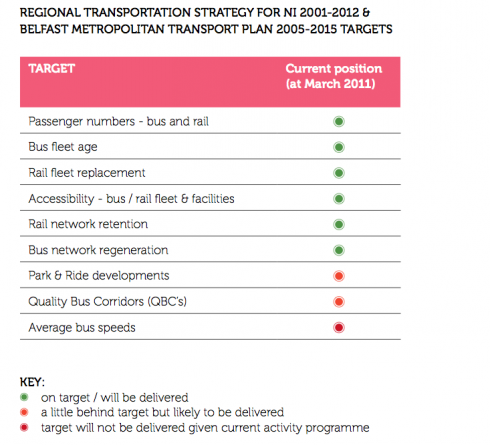

They include this diagram on Page 7.

Without numbers and context, this is ultimately meaningless. If anyone can tell me the difference between “Will Be Delivered” and “A Little Behind Target But Likely To Be Delivered”, I’m all ears.

On page 10, we’re assaulted by some more statistics. First of all – CSAT numbers are meaningless for a government-subsidised monopoly. The people surveyed likely have no choice and they have nothing to compare it to.

Translink reports there were 77 million passenger journeys in 2010/11. This sounds like quite a lot. According to NISRA, of 686,644 working persons (aged 16-74) in Northern Ireland, only 47,719 took the bus or train to work. But they’re likely to have worked probably 250 days a year, maybe more, resulting in around 2.4 million journeys just for work assuming they only took one instance of public transport to work and one instance back. My mother in law, for instance, takes two buses to work and two to return home even though she lives and works in Belfast. Add to this schoolkids, unemployed persons, the retired (who get free transport) and you can see how this stacks up. Considering that Translink is only attracting less than 7% of the NI workforce speaks about the impact it is having on the economy.

Research on a sample of key corridors shows even with bus priority measures, over a ten year period (2001-11) bus speeds have reduced on average by 12%.

Considering that the average bus speeds are much lower than they need to be (see diagram above), Translink is not a viable option for most workers in the current form. This is going to be mostly due to road contention so the question is – how do you make buses run on time during rush hour? The easy answer? Less cars on the road. So how do you get 490,260 people who currently drive (or car pool) to work to consider using the public transport network? And that doesn’t include 16,011 people who use a taxi.

On page 56, we get into the meat of the report. The issue I have with the punctuality reports is that there is no context. Ulsterbus may have a 95% on-time record but that number is meaningless without context. You can expect all of the services which run between 10 am and 3 pm to run on time. And all of the services after 6:30 pm probably run on time. But the time critical services, during rush hour for work and school runs, are where the most major impact is seen. Why not strip those figures out? Because they’re bad?

I am also amused that ‘On time’ for bus services defined as within 7 minutes of timetable; for rail services within 5 minutes (local)/10 minutes (long haul). So, even if the bus or train is late, it’s still on time.

It’s obvious that our public transport system is not busy. This indicates to me that Translink is facing a death spiral where costs will continually increase while passenger numbers dwindle (even while population increases). Translink is simply not cost effective when you take into account the relative inflexibility of public transport systems.

Translink also complains that due to the economic downturn, passenger numbers decreased. Is this not the exact opposite of what you should expect for a public transport system? I would assume that cars mean financial independence and security and that trying economic times would drive people away from the increasing costs of cars and into the welcome arms of public transport. But, it would seem, the opposite occurs.

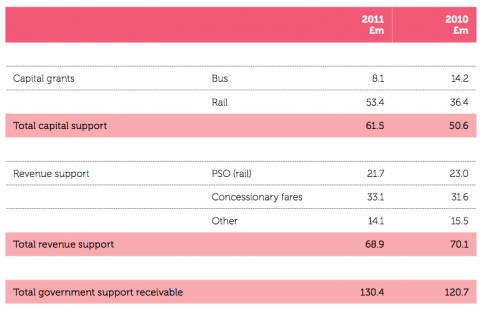

This is quite encouraging, a small loss on a large revenue. Perfect. But that’s not the whole story.

So, Translink had turnover of £187.8 million pounds and then received an additional £130.4 million to keep the service running. Considering that government is currently paying for for 41% of Translink, it’s not a stretch to imagine that they could start to pay for 100%. Especially after they realise the reduced costs in no longer needing to collect cash, issue and advertise multiple redundant promotions to sell tickets and start to monetize the service through smarter ways. And yes, we have some ideas about that.

Turning the amount of advertising Translink puts out there to advertise it’s own services into opportunities to advertise third party products to their captive audiences and, at the same time, sell premium services, seems to me like a no-brainer.

The flexibility and convenience of a car cannot be matched by public transport. This is obvious. Even when you consider the rising costs of fuel and the recent rise in parking fees, cars remain extremely competitive in the face of our heavily subsidised public transport system. For a public transport system to be used by the general public,

I want to challenge the assumption that public transport competes with private transport. It’s a different thing entirely. But there must be a way to both increase usage of public transport and convince people to use their cars less.

The question being: has anyone in government investigated this? And if not, why not?